Expansion in TeX

引入

宏展开是 中一个很重要的概念,为了引入这个概念,参加下面的例子:

1 | |

那么你猜猜,这段代码输出的结果是什么? abc ? ABC ? 结果是 abc. 我不是都让它uppercase了么?为什么还是没有uppercase,反而是给我直接输出了?

背后的原理就是宏展开, 下面我们来细说这个宏展开.

个人感觉

宏展开是可以和catcode并列的一个属于 的黑魔法, 用好了可以写出一些很 unbelievable 的代码.

LaTeX 2e

simple example

先讲一下\expandafter的作用: expand the first token after the {. 所以下面的命令:

1 | |

会先展开 { 后的第一个token,这个token就是\cmda, 于是\cmda被展开为 ‘abc’ , 从而就变成了 \uppercase{abc}了.

TeX only uppercases explicit character tokens (using the

\uccodetable)

The \expandafter primitive expands the token after the next one, 所以上述的 the next one 就是 ‘{’, 而那个after的东西就是 \cmda.

如果你的命令是 \uppercase\expandafter{abc\cmda}, 那么这个 \expandafter首先展开的其实是letter ‘a’,而不是macro \cmda. 毕竟\expandafter只负责展开它后面的第二个token (the token after the next one)

expanding process

expand rule

一个\expandafter命令可以认为包含下面这三个步骤, 针对示例: \expandafter T\cmda

- 首先把第一个token 'T’保存 (read: a\cmda)

- 然后展开第二个token ‘\cmda’ (\cmda -> abc)

- 随后把第一个token重新放到input中, 让TeX再次read (read:Tabc)

相当于一个\expandafter要吃两个参数,第一个参数先存着,第二个参数进行展开. 有了这个原理之后我们在看一看multiple \expandafter的情况. 一个具体的例子,参考自 Overleaf Understanding expandafter , 网址如下:

1 | |

定义 , 然后 ,然后使用如下的命令:

下面我们来分析这个展开的过程:

-

首先TeX在read过程中,首先读到第一个token-,然后这个 把它后面的第一个 token- save,把它后面的第二个token- 展开(执行此token).

- 现在我们进入到了展开的子过程 (这其实是一个子递归)

- 会把它后面的第一个token- save, 然后把它后面的第二个 token- 展开

- 最后这个子过程得到的token list为:

-

子过程(子递归)结束,把前面 save 的 重新 re-inserted 进 input . 所以现在的 token list 为: , TeX 继续处理这个 token list 的展开

-

对于 , 其后的第一个 token- 被 save, 其后的第二个token- 被展开.

-

token- 的展开结束,把前面 save 的token- 再次 re-inserted 进 input

-

这个过程结束得到的 token list 为:

-

这个 token list 便是最终的展开结果 , 其实可以把最后的展开结果总结为 :

把上面抽象的分析实体化为一个具体的实例如下:

1 | |

最终得到的结果就是: Hello, world

也就是只加粗了第一个字母 ‘H’, 可以对比如下命令的结果来理解:

- \foo\bar: Hello, World

- \expandafter\foo\bar: Hello, world

这样也许你就能看出\expandafter到底有啥作用? 到底是怎么作用的 ?

别忘了 \expandafter 命令本身就可以看作一个 token

其实LaTeX2e中有一个比较好用的命令: \@expandtwoargs, 可以在命令把这两个参数吃进去时,提前展开这两个参数

突然感觉这个\expandafter 应该改名为\expandfirst了. 但是如果从整个命令的角度来看,就是 \uppercase operation expand after macro \cmda: means that \cmda will expand first.

read expand CS

现在分享一个怎么读懂别人\expanafter 代码的方法,这个案例是本博客后续会用到的一个回答,代码如下:

1 | |

我们重点分析那一长串的 \expandafter, 这里先给出我的一个分析方法:

-

从左往右,依次划掉 “1个 \expandafter + 1个 token”

-

最后从后往前分析,把之前划掉的 token 一步一步的加回来(如果划掉的token是 \expanafter 也要加回来)

所以你可以按照如下过程分析:

1 | |

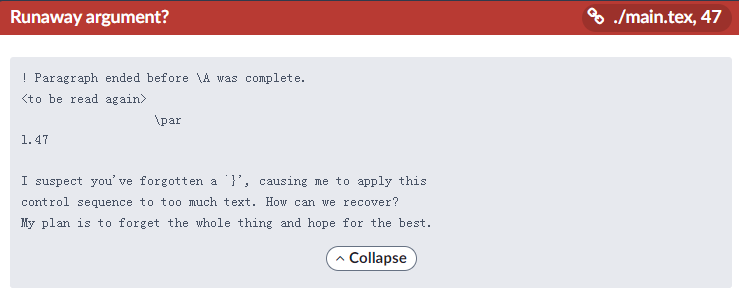

因为最后的一个 \pempty 虽然被 \protected 保护了, 但是使用 \expandafter 仍然可以把它给展开. 于是我们一步一步的加回来被划掉的 token,过程如下:

1 | |

所以最后得到的结果就是:

1 | |

第一个命令 \withedef 中的 \pempty 由于被 \protected 了,所以不能被 \edef 给展开.

因为 \pempty 是一个macro,所以它和后面 ‘x’ 之间的空格会被吃掉

write expand CS-I

我们当然不能局限于仅仅只是看懂expand,很多时候其实我们需要的是自己去写这个expand,知道了原理之后其实并不复杂. 就以前面的那个

1 | |

为例. 为了一步一步的引导新手怎么写这个\expandafter,我们先从一个简单的例子开始. 下面这个代码片段是错误的:

1 | |

怎么把这个展开写正确? 在此之前,让我先给出我总结这个规律:

在一个要被前一个\expandafter展开的 token 前添加一个\expandafter,可以让这个 token 后面的宏提前展开

在这里的情况就是:上述的expand会去展开字母 ‘a’, 但是我们想要的是去展开 ‘a’ 后面的 macro \cmda, 那么就需要让这个\expandafter的展开对象后移1个 token. 所以只需要在这个 ‘a’ 的前面添加一个 \expandafter 即可,所以正确的代码为:

1 | |

好,现在增大难度,有两个letters “ab”, 如果直接像下面这样写:

1 | |

那么\uppercese后面的第一个 \expanafter 回去展开 ‘b’, 和前面类似,我们需要展开的对象后移一个 token; 所以直接在 ‘b’ 的前面加上一个 \expandafter, 正确的代码如下:

1 | |

所以对于三个letters下的正确展开代码就是:

1 | |

所以最后看来:命令\expandafter展开 token 的过程就是以 token 为单位,从左至右,跳着展开的.

write expand CS-II

本节内容部分参考自问题: 多个\expandafter的展开过程是怎样的

引入

首先介绍三个宏的逆序展开,并且以此来总结一个规律用于之后的代码书写. 为了代码的书写方便,进行一定的记号规定

- \let\ep\expanafter

<A>表示宏\A的展开内容

下面即为代码展开过程的详细说明:

1 | |

所以从上面可以发现一个总结出如下的展开规律:

- 位于偶数位置的 token 均被 save 了,位于奇数位置的则被展开了(跳着生效,跳着展开)

- 被展开的

\ep直接扔掉,被展开的宏内容就保留下来

逆向分析

下面就运用上面总结的规律构造四个宏逆序展开的代码:我们要构造四个宏的逆序展开命令(*),那么四个宏对应的命令展开一次后就会得下面的这个序列(因为第四个宏最先被展开):

1 | |

后续为了讲解的便利,我们把 (*) 看作公式编号

又因为(*)是跳着展开的,所以上述序列-(**)就位于原序列(*)的偶数位置. 为什么没有出现第四个宏? 因为第四个宏 \D 已经被展开为 <D> 了,而(**)中仅包含被 save 的 token. 于是添加等数量的 \exp 即可确定原(*)序列为:

1 | |

其中高亮部分就表示(**)中的元素, 从而格式化后原逆序展开四个宏的代码为:

1 | |

后续会说明为什么这样写代码,部分情况你可能需要在每一行的末尾加上 % 注释掉多余的空格.

统计规律

下面我们总结个宏逆序展开的规律,得出这种类型宏的写法:

1 | |

下面来统计每一行的 token 数目,下面不同 值下统计的 token 数:

1 | |

所以逆序展开 个宏总共所需的 tokens 数目 为:

然后统计每一行的 \ep 个数 可以发现, 从下到上每一层 的 \ep 数量为:

所以今后写这种宏就可以按照这种规律来写了,但是部分的问题可能还的具体分析吗,不可能情况下都是最简洁的.

跳跃展开

之前都是反正,正向顺序一词展开的, 那么如果是我要求展开顺序为: 呢? 你肯定不能把原始命令 (*) 写成下面这样:

1 | |

写成这样都不一定能运行,毕竟这些 token 的顺序不一定能够交换(也就是输入的格式必须为:\A\B\C). 那么怎么写? 我们采用逆向分析的方法, 一步一步的反推展开前的控制序列.

先不考虑 \A 命令的展开,因为是先展开 \B, 然后再展开 \C, 所以原控制序列 (*) 展开一个宏后得到的结果 (**) 肯定是:\A\ep<B>\C,再添加对应数量的 \ep 后可以得到展开前的原控制序列 (*) 为:

1 | |

但是现在还有一个问题:如果 TeX 再去读取 \A\ep<B>\C 这个结果,那么它会先去展开 \A, 所以我们的想办法让 \A 后面再展开。于是就必须在 \A 前要加上 \ep. 所以考虑到 \A 的展开顺序,那么展开后的命令 (**) 为:

1 | |

具体到每一个宏,从左到右其展开前应为:

\ep\ep:因第一个\ep保留,故它是偶数\ep\A: 保留\ep\ep:保留\B\ep: 因被展开,故奇数,后面加\ep\ep\C: 保留

所以最终的原始控制序列 (*) 为:

1 | |

注意

- 其中那个

\ep的作用是为了占位,为了防止这个占位\ep对其他内容产生影响,可以考虑在\C后加上\empty等类似的宏. - 如果不添加这个占位,那么最后的

\C其实也可以保留下来(只要对应的宏\C能被保留,也就是保证其在原序列中位于偶数位置),代码如下:1

2

3

4

5

6\ep\ep\ep\A\ep\ep\B\C (*)

% format code

\ep\ep\ep\A

\ep\ep\B

\C

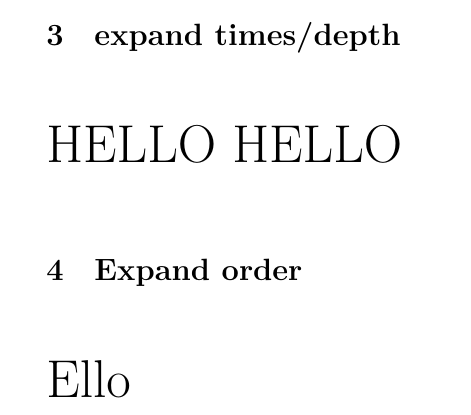

检验代码是否正确

为了检验我们这个代码是否正确,我写了一个 mwe 用于测试,如下:

1 | |

上述构造的三个宏 \A, \B, \C 的作用和效果见源代码注释. 这里的重点是检测宏的展开顺序,如果是 \B 最先展开,那么它必然会把后面的 \C 这个 token 给吃掉,但是 \B 什么都没有留下,也就导致了后续 \A 展开的过程中没有参数的传入,导致报错. 但是如果是 \C 先展开,那么 \B 就只会吃掉对一个的 token ‘H’, 后续的 \A 会把剩下的 ello 的第一个 token 给 uppercase 了.

最后的运行结果如下:

总结

- 其实就是从结果去一步一步倒推上一步,在这个过程中考虑一下奇偶

token. 毕竟奇偶涉及到这个token是保留还是展开. - 如果多个

\ep分布的较为稀疏,那么它们可能就是多个组,并不是一个组前面的命令\uppercase\ep{\cmda}和这里的\ep命令也是相同的,只不过上述的{就是这里的\A,\cmda就是上述的\B.

突然发现之前也没有遇到这种多个宏展开的问题了

noexpand and protect

如果你不想提前展开某些 macro 呢? 这个特性在 TeX 中其实是随处可见的,比如常用的 \thepage 命令,如果我们设置这个 macro 为具体的数值肯定是不行的,这个 \thepage 的数值得随着不同的页面变化. 可以认为这个 \thepage 里面就有一些 macro 没有被完全展开,它们只有在打印具体的页数的时候才会被完全展开.

这个机制应该就叫做 lazy evaluation 吧, 类似于 mma 中的延迟赋值 f[x_] := x;

再来一个简单的例子:

1 | |

上述定义的\cmdb就是没有被展开的例子, 当我 \cmda 重定义为"A"后,对应命令 \cmdb 也会被重定义为 “A”.

这里可以介绍几个基本的命令:

-

\noexpand: prevents doing an expansion of the next token (only one token).

-

\unexpanded: e-TeX includes an additional primitive \unexpanded, which will prevent expansion of multiple tokens.

既然都说到这里的,就必须要提到这一系列命令了: \def, \gdef, \edef, \xdef. 以及对应的 e-TeX 拓展的命令\protected 了. 这里必须抄一段了,代码来自: When to use \edef, \noexpand, and \expandafter? :

The prefix \protected can be used before \def and friends to define a protected, i.e. “robust” macro which doesn’t expand inside an \edef context (like in \write). However, \expandafter does expand such a macro.

- 这个所谓的 robust 在你们刚入门的时候应该也不理解吧

- 所谓的 \xdef 可以看成是 \gdef 和 \edef 的结合体

further reading

更多的详细教程可以参见: Overleaf Articles, 里面有挺多不错的东西.

LaTeX 3

introduction

在LaTeX 3中是可以很方便的操控宏展开的,可以有如下的途径:

1 | |

这5个命令用的好,就不用担心绝大部分的展开问题了. 第一个 \exp_not:N 可以控制一个宏不被 e-type 或者是 x-type 展开.

Expand

expandable variable

部分用户也许经常在 interface 3 中看到诸如下面这样的 TeXhackers note, 下面这个例子是 \tl_tail:N 的 note:

The result is returned within \exp_not:n, which means that the token list does not expand further when appearing in an e-type or x-type argument expansion

我们下面就写一个具体的例子来说明这个 note 到底说了怎样一回事:

1 | |

这段代码的结果是: macro:->b\l_tmpb_tl; 因为 \tl_tail:N 的结果是 \l_tmpa_tl, 而这个宏是 within \exp_not:n 的,也就是说:上面 \tl_set:Nx 这一行其实等价于:

1 | |

这样我们的 \l_tmpa_tl 中的第二个 token 自然就是 \l_tmpb_tl 的原始定义了,而不是 b.

被 \protected 的宏也不会被 e-type 和 x-type 展开; 故而 xparse 提供的 \NewDocumentCommand 等一系列的命令定义的宏和被 \noexpand 修饰定义的宏无法被正常展开.

注意区分 \protect 与 \protected; 这两者是没有关系的, \protected 的作用机制和 \long 的类似。还可以这样理解: 前者是 LaTeX 内部提供的为了弥补没有 \protected 宏的一个 trick,后者是 eTeX 提供的; 对于 \protect, 它会在 normal context 中,它会被展开为 \relax; 在部分特殊的 context 中会被定义为 \noexpand\protect\noexpand, 在部分的 context 中也会被定义为 \noexpand.

详细信息,可以参见:why do we need \protect (可以认为这个参考样例中的 \protect 起了一个传递作用,为了把 \noexpand 传递到第二个过程中;个人觉得也可以在第一步传递一个 \foobar 过去,得到 \foobar\foo, 然后在把行命令写到 toc 文件之前,把 \foobar 定义为 \noexpand 也行。但是两次都用 \protect 我觉得更好,更加的统一.)

下面就是一个示例:

1 | |

运行结果:

1 | |

如果把上述的 \noexpand 去掉,那么 \cmdb 就会被展开为 CMD-B. 可以参见前一节: “noexpand and protect”. 然后再来说一下这个 robust,见示例:

1 | |

对应的输出为:

1 | |

我们也可以用 \MakeRobust这个命令来让一个已经存在的 fragile command 编程 robust command.

expandable function

把 LaTeX 中的宏划分为 Variable 和 Function 是不太准确的,但为说明 xparse 宏包中 \NewExpandableDocumentCommand 等系列命令存在的意义,我这里就认为的进行了划分,并且 LaTeX 3 中也是区分了变量和函数的.

大部分的用户如果弄不清一个函数是不是 expandable 的,那么建议你一律使用

\newcommand.

一个函数是 expandable 的,就意味着你可以直接把这个函数当成一个值(前提是你的函数要有返回值,并且处于一个expand 的 context 中)直接在一个表达式中参与运算, 而不用再新建一个变量来存储这个函数返回的值,然后再用这个新的变量进行表达式的操作.

一个普通示例:

1 | |

运行结果:

1 | |

从 TeXLive 2019 开始, pdfTeX, XeTeX, LuaTeX 中提供了 \expanded 这个primitive (最开始仅在 LuaTeX 中可用, 更多的信息可以参见: Does \expanded replace the \romannumeral trick for expansion?), 这个 primitive 和 LaTeX 3 中的 e-type 是密切相关的,可以说这就是后者的基础.并且也是 e-type 和 x-type 的一个重要区别(LaTeX3 中 \tex_expanded:D 的原定义即为 \expanded).

\expandedgives a nice mix of both\edefand\romannumeral, allowing us to get the full expansion of a token list while being itself expndable

在介绍之前,先复制粘贴几个 interface 3 中的 remark:

- Fully expandable functions (★): Some functions are fully expandable, which allows them to be used within an x-type or e-type argument (in plain TEX terms, inside an \edef or \expanded), as well as within an f-type argument. These fully expandable functions are indicated in the documentation by a star(★)

- Restricted expandable functions (☆): A few functions are fully expandable but cannot be fully expanded within an f-type argument. In this case a hollow star(☆) is used to indicate this

好了,接下来我们看看 \expanded 的使用方法:

1 | |

运行结果:

1 | |

expand or excute

关于 expand 和 excute 的区别? 目前我觉得 expand 就是替换,而 excute 就是“吃(前面被展开的)参数”,这个参数可以是一个控制序列,也可以是一个 token list. 比如下面这个case:

1 | |

如果在 expand only 的 context 中,\def 并不会把 \foo 这个token 吃进去,返回会留在这个;然后再继续去展开这个 \foo 如果 \foo 没有定义,那么必然报错.

那么哪些 context 是 expand only 的呢?常见的有:

\edef\write\csname \endcsname- 我们前面讲到的

\expandafter fandespecifier in LaTeX 3.

所以这个时候我们也许就需要另外一个 data type 了: Expandable flags. 看看文档中对这个 data type 的定义:

Flags are the only data-type that can be modified in expansion-only contexts.

但是我们也不用太过担心这个 expand only, 一般都是 kernel 或者是 toc 之类的东西才会涉及到. 普通情况下用 int, 或者是 boolean 之类的就行了.

\exp_after:wN

为什么是 \exp_after:wN 不是 \exp_after:NN. 因为这个命令的第一个 token 可能是 {, } 或者是一个 N-type 的东西. 详细信息可以参见: Why is \exp_after:wN named \exp_after:wN ?

一个简单的使用示例:

1 | |

不推荐使用 \exp_after:wN 这个命令(除非万不得已),推荐使用 \exp_args:N<...> 及其 variant. 可以参见 interface 3:

\exp_after:wN ⟨token1⟩ ⟨token2⟩Unless specifically required this should be avoided: expansion should be carried out using an appropriate argument specifier variant or the appropriate

\exp_args:N⟨variant⟩function.

argument specifier

Introduction

下面讲解一些关于 argument specifier 的东西,毕竟这个东西你是必要要学会的,如果你要使用 LaTeX 3 中的上面两个命令的话. Every function must include an argument specifier. For functions which take no arguments, this will be blank and the function name will end :.

-

N and n: means “no manipulation”, pass the argument through exactly as given

-

c: means “csname”, argument be turned into a csname. like

\csname mycmd \csname. -

V and v: means “value of variable”, get the content of a variable:

Vargument will be a single token (similar toN), usingva csname is constructed first, and then the value is recovered. So1

2

3% 两个等价的命令

\foo:V \MyVariable

\foo:v {MyVariable}You can only define a base function argument is

ninstead ofv,x,e,oetc. Then generiant the variant(onlyncan be variant). -

o: means “expansion once” (Is it equvilant to expand only the first macro once?), while that

V,vare prefered. -

x: means “exhaustive expansion”, fully expand every macro(until only unexpandable ones remain). Functions which feature an

x-type argument are not expandable. -

e: means “expandable functions”, The

especifier is in many respects identical tox, Functions which feature ane-type argument may be expandable. Besides, Parameter character (like#1,#2, …) in the argument need not be doubled (when in nest loop). -

f: means “first token expansion”. The

fspecifier stands for full expansion, and in contrast tox, this type stops at the first non-expandable token(<space>is gobbled) (reading the argument from left to right) without trying to expand it. -

T/F: Ture/False in logic test.

-

p: means TeX “traditional parameters”, like

1

\cs_set:Npn \foo:n #1{\textbf{#1}} -

w: means “weird arguments”, This covers everything else, but mainly applies to delimited values

当然,这个函数名其实也不一定要以 : 结尾, 详细信息可以参见: Create Macro in LaTeX. 最后,再来看一个来自 interface 3.pdf 和 expl3.pdf 中关于 signatute 的简短总结:

Nis used for single-token arguments whilecconstructs a control sequence from its name and passes it to a parent function as anN-type argument.- Many argument types extract or expand some tokens and provide it as an

n-type argument, namely a braced multipe-token argument:Vextracts the value of a variable,vextracts the value from the name of a variable,nuses the argument as it is,oexpands once,fexpands fully the front of the token list,eandxexpand

fully all tokens (This type is not nestable, thusx-type does not work ineorx-type, whilee-type does work inxande-type; And it can only be used to create non-expandable functions). - A few odd argument types remain:

TandFfor conditional processing, otherwise identical ton-type arguments,pfor the parameter text in definitions,wfor arguments with a specific syntax, andDto denote primitives that should not be used directly.

In almost all cases,

e-type should be preferred,x-type retained largely for historical reasons, and should where possible be replaced by thee-type equivalent. — Fromexpl3.pdf

Generate variants

First of all, only n and N arguments can be changed to other types. The only allowed changes are:

cvariant of anNparent;o,V,v,f,e, orxvariant of an n parent;N,n,T,F, orpargument unchanged, useful in command\cs_generate_variation:Nn, see LaTeX3 variants with TF arguments.

f-type

f-type 这一个argument specifier 可能比较奇怪,但是可以参见如下的示例:

1 | |

最终的结果为:

1 | |

所以把这个f-type 看作 (first) expansion 个人觉得还是比较好理解的.

e-type/x-type

See blog: Get the Jag: from x-type to e-type for more info. Thus in most case, use e type instead of x type.

w-type

本节参考:

什么时候应该使用 w - type ? l3styleguide 中描述到:

When defining commands that do not follow the usual convention of accepting arguments as single-tokens or braced-text, the

wargument specifier is used to denote that the function signature cannot fully describe the syntax.

也就是说你定义的函数接受参数的行为很 奇怪 的时候,也就是你的参数不是以下的情况:

- single token,

<single char>,<single CS> - braced-text,

{<arg>}

每一个 w-type 的 function 都尽量在最开头的位置说明其语法,不然别人阅读时可能就不知道你这个函数的参数到底是怎么 接收 和 处理 的. 比如下面的例子:

1 | |

如果你不知道函数 \foo:ww 的定义,那么你有极大的可能无法写出正确的参数(传递)形式.

其实就是你不会写出

23这个 explicit text, 从而导致#2不能被正常的解析

这个 w-type 和传统的 p-type 还是比较类似的,有趣的是,w-type 会常常和 quark 共同出现, 比如把\q_stop 作为一个分隔符的存在 (delimiter) . 当然你也可以定义其它的分隔符命令, 可以参考下述这个 l3kernel 中的例子:

1 | |

然后这个函数在 l3kernel 中的使用方法为:

1 | |

有了这个例子作为参考,就很好理解这个 w - signarture 了.

不然 excute 一个 quark,因为 quark 的定义方式类似:

\def\foo{\foo};一旦 excute 一个 quark, 就会导致无限循环.

如果定义的使用了 w-type, 那么你极大可能是为了完成一些 参数解析 的工作。所以一般情况下写一个 w 参数就行了, 比如这样:

1 | |

而且并不推荐在一个 w-argument 后接太多的其它 signature, 比如:

- \foo_bar:wnw

- \foo_bar:ww

这两种写法都是不推荐的. 但是有时候你可能会看到 :wn, :wN 这种类型的 signature. 比如 \exp_after:wN.如果你拿不准主意,就直接写 :w 就好了,不用管其它的.

关于参数解析,或者是参数预处理器,可以使用 xparse 中的 processor, 也可以依托于 xparse 来定义你自己的 processor.